The Mary Celeste was not the last ghost ship found

near the Azores.

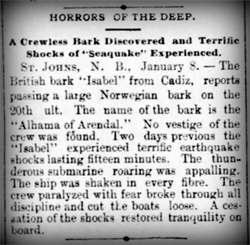

The crew of the bark Alhama of Arendal, sailing from

Norway, abandoned their ship during a violent seaquake

on December 20th, 1885, 13 years after the ghost ship

Mary Celeste was found deserted.

Evidence of a Seaquake

Some time after eight in the morning on the 25th something dreadful happened on board the Mary Celeste causing an experienced master mariner to place his wife and 2-year-old daughter and seven other adults besides himself into a yawl with limited freeboard, and hastily abandon a perfectly sea-worthy, 101-foot, 282-ton vessels. The Captain had to believe, as everyone else, that staying aboard the Mary Celeste was extremely dangerous.

As the Dei Gratia salvage crew noted that most of the sails were furled when the Mary Celeste was found, which leads one to believe that whatever had happened on board, happened moments before they departed the lee side of Santa Maria.

Likely, while hoved-to near shore or anchored, Sarah, the captain's wife, tended to Sophia, her child, as the cook prepared their first hot meal in days. After the crew ate, they took a well-deserved smoke break and the cook cleaned the pots and stowed things away. Then, sometime after 8 AM, the captain gave the orders to pump the bilges and run up the sails, putting order back into the Mary Celeste.

Knowing their new course to be a safe one, he took his wife and retired for a nap, leaving the first mate in charge with instructions to call him only if needed. We know this because the Captain's bed was unmade, something that never happened on board a well-run ship in 1872 unless the Captain was in the bed or intended to go back to it later.

The seaquake erupted just as the Mary Celeste was about to leave.

The ship shook violently, knocking her wooden compass stand over and breaking the compass housing.

The vertical motion in the sea bottom transferred to the ship and bounced the large drinking-water cast loose from its chocks on the main deck, and danced the huge cast-iron galley stove out of its chocks, likely flinging open the stove door or bouncing one of the top lids off to the side, allowing smoke and embers to whirl out of the stove.

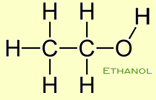

The severe vibrations also jarred the barrels of alcohol she carried, loosening the stays on nine barrels, spilling almost 500 gallons of raw alcohol into the bilge.

The men pumping the bilge were so scared that they stopped what they were doing, leaving the sounding rod and the bilge valve on the deck.

The sailors up in the rigging, in the process of setting the foresail and upper and lower topsail, were jolted so hard that they fell into the sea or landed hard on the deck, explaining why the fore lower topsail was only partly set. The foresail gear was left dangling, which tells us why the gear was later found broken with the clew lines and bunting gone. The fore-braces on the port side were placed out-of-order, no doubt due to the hysteria of the men. Some of the other running rigging was left hanging loose for the same reason, which explains why two sails apparently tore away from the yards and blew overboard during the time the Mary Celeste sailed as a ghost ship.

Bradford was right in his book when he said the cause of the disaster was an "outside destructive force," not something within the ship. However, he made a mistake in developing his waterspout theory by assuming the blown away sails meant only one thing - excessive wind. He never reasoned that, in a normal breeze, a loose flapping sail could be torn away and/or ripped to shreds within a few days if not set properly.

The leading theory up until Bradford published his book was that alcohol fumes were somehow responsible. He belittled this idea by pointing out that, if any alcohol had leaked into the bilge, it would be pumped out every day with the bilge water. If there had been an alarming smell of alcohol, Bradford reasoned, the seamen would have notified the captain and they would have vented the bilge at all cost. The alcohol expert consulted by Bradford added that, in his opinion, had there been a dangerous alcohol leak, there would have been an explosion and a fire leaving no doubt about the cause of the abandonment. No one realized that a violent shaking of the cargo during a seaquake would cause nine barrels of alcohol to empty into the bilge in less than a minute.

There can be little doubt, the hull of the Mary Celeste, like an echo chamber, thunderously reverberated the hammering on her bottom planks, inciting the God-fearing crew to think judgment day had arrived.

To make matters worse, the vibrations likely caused mental confusion making it more difficult for the officers to decide on the proper action. In such a moment one would also wonder how well the German crew understood orders yelled at them in English.

Before the first shocks ended, the entire ship began to permeate with alcohol fumes. Fearful of an explosion, the crew dropped whatever they were doing and ran to open the fore hatch to inspect the cargo, throwing the hatch cover to the side. They also quickly opened the lazarette hatch, and the fore and aft skylights in an attempt to air out the lower decks. However, they did not open the main hatch because the yawl was still lashed to the cover.

Shortly after the main shock, the aftershocks began causing more smoke, embers, and sparkling bits of burning wood to billow up from the hot stove. Maybe William Head was brave enough to close the stove as best he could but it is doubtful he or anyone else lingered in the galley for any length of time. The fear of catching on fire in a pending explosion would have caused any member of the crew to stay as far away from the galley as possible. No wonder they did not take any personal items since they had to pass by the dancing stove to get to their chest in the forecastle.

No mention was made of the condition of the stove's flue or what type of flue system vented the stove. Nevertheless, one would expect some means of exhausting the burning ashes and smoke since the galley was setting just below the canvas. Whatever matter of venting was likely lost when the vertical vibration shook the stove out of its chocks. Other safety standards, such as shielding and other means of fire prevention, was also likely breached when the stove jumped up and down on the galley floor. Under such a situation, the alcohol fumes could explode at any second and everyone knew it.

Captain Briggs did the only rational thing he could do. He yelled out the orders to abandon the Mary Celeste.

In a mad dash, someone grabbed an ax and quickly cut the yawl loose from the main hatch and everyone helped drag it over to the starboard rail. At this point, the man with the ax grabbed the main peak halyard from the belaying pin in the pin-rack, played-out a good section, placed the line on the rail and whacked it through, at the same time, making a deep cut into the rail. He let the loose end go, took the end of the line he had just cut off the halyard and tied it to the yawl.

They heaved the yawl over the starboard side and secured it with the line cut from the halyard. The Captain put his wife and daughter in the small boat, snatched his chronometer, sextant, and the ship's papers and jumped in. The crew joined them.

At this point, Sarah praying and Sophia screaming and everyone else near panic, one of the crew secured the other end of the halyard to the rail and the yawl drew away. This was the standard procedure in those days when a ship caught fire. The idea was to tie your lifeboat a safe distance off the stern and hope the fire went out before the vessel burnt to the waterline. The crew could pull themselves back on board when the danger was over and claim salvage to whatever remained.

However, as luck was going for the crew of the Mary Celeste, another aftershock might have occurred, sinking the yawl, turning its mass into a sea anchor and ripping the halyard loose from the rail.

But what are the odds that an aftershock sunk the little boat immediately?

The problem in recreating what might have happened on the yawl is that we have no real description of this vessel. The info given by others is that the boat is 15 to 20 feet in length without mention of whether it is a rowboat or a sailing yawl. If we assume Captain Briggs was not a complete idiot, then we must also assume the yawl was capable of carrying everyone. It was likely closer to 20 feet in length and carried a sail along with at least one set of strong oars, maybe two. There might have also been emergency provisions stored on board. The boat was likely lashed to the main hatch because it was too big to fit on the stern davits. If the yawl was a large 20-foot lifeboat, we can take a different view of what might have happened to the crew after they departed the Mary Celeste, especially considering what was written in the Liverpool Daily Albion on 16 May 1873:

Was this the fate of the people on board?

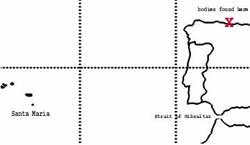

A sad story of the sea - a telegram from Madrid says 'Some fishermen at Baudus, in Asturias, Spain, have found two rafts, the first with a corpse lashed to it and an Agrican [American?] flag flying and the second raft with five decomposed bodies. (see chart) It was not known to what vessel they belonged;

The American flag normally carried on board the Mary Celeste was missing. No mention was made as to how long the bodies might have been "decomposing." The bodies were supposedly buried near a church in Baudas.

Suppose, at about the same time you realized the mother ship was not going to explode, the halyard securing the yawl to the stern of the Mary C somehow parted or came unknotted. You realize you forgot to lash the wheel properly, something a good Captain would have done. What do you do now if you're Briggs? Would you try to catch up with your vessel and your valuable cargo, hoping the wind would change and turn her back into your little boat? Or, would you turn the yawl about and head back to the safety of Santa Maria? Capt Briggs had his sextant and charts. They would try to catch the Mary Celeste. Might they have lived for weeks on rainwater and fish? Could the yawl have broken apart in heavy seas? Could the survivors have lashed together two crude rafts and drifted for a long time before being found off the Coast of Spain?

Mary Celeste sailed ~370 nautical miles in a westerly direction as a ghost before being found nine days later. Those who think it impossible for her to travel so far in such a short period with only two small sails set should realize that she was carried more by the Azores Current than by the wind.

The main Gulf Stream passes close to the Grand Banks, south of Newfoundland, where it branches into two currents: the North Atlantic and the Azores Currents. The North Atlantic turns north just east of Newfoundland and flows east toward the British Isles. The Azores Current flows east at about two nautical miles per hour past the Azores Islands towards the shores of Portugal before turning south.

Carried by the Azores current, the Mary Celeste could have traveled up to 50 nautical miles per day making it reasonable that a Dei Gratia came upon her where she did.

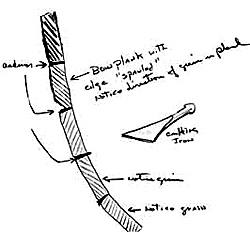

Explaining the Cuts in the Bow Planks

John Austin, Gibraltar's Surveyor of Shipping, testified that he found on the bow, about two and one-half feet above the waterline on both sides, a long narrow strip, at the edge of a plank under the cat-head, cut away to the depth of about 3/8 inch and about 1 1/4 inches wide for a length of about six to seven feet. He professed intense bewilderment as to the tool used to cut such marks and why they would have been cut in any vessel at these locations.

Captain Winchester, one of the owners of the Mary Celeste, had a different opinion. He agreed with Captain Shufeldt, who had determined that the injury was actually splinters or splints that had popped off the wood, which had been steamed and bent to curve the bow when the boat was recently rebuilt.

The Mary Celeste had been "on the rocks" several times in her long history. She also had been involved in two collisions, one of them recent. According to testimony, just before this trip, she had been purchased at a salvage auction in New York for $2,600 and rebuilt for $14,000. Her rebuilt condition was confirmed by the crew of the Dei Gratia when they said, "Her hull appeared to be nearly new."

The condition of the hull

We can assume that many of her bow planks were newly replaced. They were probably cut from black spruce, a long-fibered wood used most often in the construction of ships along the Northeastern Coast and in Newfoundland. Slight ring failure along the grain might have occurred in the planks while they were still curing in the repair yard. Even if they were perfect boards, the steaming and bending of the planks to fit the contour of the hull would weaken the grain.

The caulking done during her recent rebuilt could also have been responsible for the edges of the planks to splinter out. Caulking was an extremely important process, not only because it rendered the vessel watertight, but also because driving the oakum between the planks put great pressure on and squeezed them together tightly, holding them in tension adding to the rigidity and strength of the vessel.

During caulking, it was very important to allow for expansion of the planks when wet, especially if the grain ran in a direction that made splintering likely. If too much oakum was pounded in between the planks, then a condition of excessive stress would have been established at the edges of the replaced planks. As these planks soaked up water, the stress would increase.

Accordingly, it is not surprising that during the severe vibrations of the seaquake, long splints would pop from the edges of a few bow planks along the grain, appearing as if it were cut with an unknown instrument.

/to be continued ...

The graphics and text on this page was taken from Captain Williams DeafWhale website, which has been archived. All opinions expressed are his and he retains the copyright of this material.